Growing my Grass Shader

• By: Aleksandar Gjoreski

When I think of grass, I picture wide fields, uneven ground, a gentle wind moving through everything at once.

Something soft, alive.

That image has been with me since the very beginning of Revo.

Long before there was a player, a world, or even a proper camera, I knew I wanted vegetation to be a core part of what would become my most challenging project so far.

Grass especially. Not as decoration, but as something that fills the space and gives the world a sense of scale and calm.

When I started working on it back in January, right after setting up Three.js and Rapier, grass was the first thing I touched (pun intended).

I didn’t have a plan yet. I just wanted to see something green move on screen. A few instanced triangles, some subdivision, a bit of noise-driven motion, nothing fancy, but enough to feel like a starting point.

It looked nice… for a moment.

Then I did what everyone eventually does: I tried to scale it. And that’s where things got interesting.

Frame rate dropped, the laptop warmed up, fans kicked in. The illusion didn’t hold once the grass stopped being a small patch and started behaving like an actual field.

What you see below is the result of going back to that idea many times over the past year. Not all at once, and not always deliberately. Sometimes out of curiosity, sometimes out of frustration, and sometimes simply because I wanted it to feel better than it did before.

Showcase of the current version (not published yet at the time of writing)

This is the version I’ve been working on recently. It’s part of a broader rewrite of Revo, where I’ve been revisiting old systems with a calmer mindset and a bit more experience.

It’s not live yet, and it will probably keep changing, but it’s the first time the grass feels close to what I had in mind from the beginning.

This article is an attempt to write down what I learned along the way. Not as a guide, and not as a definitive solution, but as a collection of decisions, trade-offs, and small realizations that slowly shaped this system into something I’m happy with.

I’ll start by setting the context and the rules of the world this grass lives in, and then dig into the parts that actually made a difference, especially the ones that took me the longest to get right.

0. The rules of this world

Before getting into how the system works, it’s worth pausing for a moment to describe the world this grass lives in. Many of the decisions that follow only make sense with that context in mind.

At the time of writing, in my current (still work-in-progress) scene which I don’t plan on crowding anyway, the grass alone accounts for a bit over 8.2 million triangles in a single draw call, and I can hold a stable 120 FPS on my M2 MacBook Pro.

I did experiment with pushing it further, and while it can go beyond that (FPS slightly drop to 110 with ~60 million triangles, just to give a rough idea), I eventually settled on four segments per blade and a bit over one million instances as a good balance: smooth enough for wind motion and dense enough without adding work that doesn’t really show.

Those numbers aren’t here as a benchmark or a claim. They’re just a snapshot of where the system currently sits, and they help frame the choices I’ll talk about next.

More importantly, this grass system isn’t trying to solve the general case.

The camera has a fixed height and pitch, and it always stays behind the player. There’s a single dominant light source, the sun, and the visual direction leans stylized rather than physically accurate. Above all, performance is treated as a first-class constraint, not something to patch later.

These rules might sound limiting, but in practice they’re freeing.

Knowing exactly how the camera behaves means I don’t have to design for every possible viewpoint. Knowing that the grass doesn’t need to react to fully dynamic lighting lets me simplify shading decisions. Knowing the player will never orbit freely or look straight down removes entire classes of problems before they even appear.

Once I stopped thinking of these as compromises and started treating them as the rules of this world, a lot of decisions became clearer. The goal was never to build the most general grass system possible; it was to build the right one for this world.

Everything that follows builds on that idea: fewer assumptions, fewer moving parts, and spending GPU time only where it actually shows.

1. I kept blaming triangles

For a long time, I was convinced that triangle count was my main problem.

It felt like the obvious culprit: more grass meant more blades, more blades meant more segments, more segments meant more triangles, and more triangles surely meant worse performance. That line of thinking is not entirely wrong, but it turned out to be incomplete, and in my case, misleading.

Modern GPUs are extremely good at processing vertices. They’re built for it. With instancing, coherent memory access, and relatively simple vertex work, pushing a few million triangles isn’t that dramatic anymore, especially when everything stays on the GPU and avoids round-trips to the CPU.

What GPUs are not particularly fond of is doing the same work over and over, only to throw the result away.

That’s where my mental model started to crack.

Grass is a near worst-case scenario for this kind of waste. Even with a fixed, elevated camera at roughly 50°, blades overlap heavily in screen space, especially close to the player, where they occupy large portions of the framebuffer. Thin geometry stacks up in depth, many blades sit behind others, and the same pixels end up being shaded multiple times.

Farther away, blades do collapse and overlap more densely, but they also shrink rapidly in screen space. Near the camera, that collapse hasn’t happened yet, and fragment cost scales with screen coverage, not blade count. That’s where the real pain shows up.

In my earlier versions, I made things worse by using fragment-level discard in places where I already knew a blade

shouldn’t contribute visually, guaranteeing that the fragment work had already happened before being thrown away.

So while I kept looking at triangle counters, the GPU was busy doing something much more expensive: running the fragment shader over and over again on pixels that would never make it to the final image.

Once I reframed the problem from “how many triangles am I drawing?” to “how many times am I shading the same pixel?” a lot of things suddenly started to make more sense.

This didn’t mean triangles stopped mattering altogether. Blade width, segment count, and density still play a role, and finding a reasonable balance is important, but they weren’t the bottleneck I thought they were.

The real cost was hidden in overdraw: shading the same pixels over and over, only to throw most of that work away.

This moment of enlightenment shifted the focus of the entire system. Instead of obsessing over geometry counts, I started asking a different question: how can I avoid doing work I already know won’t matter?

2. Out of sight, out of the pipeline

Once I started looking at the problem through the lens of overdraw, a very natural question followed: if a blade is not meant to be visible, why am I letting it go all the way through the pipeline?

First thing that came to mind was frustum culling. A visibility check done CPU-side which tests the bounds of a mesh with the camera frustum volume and only if the object intersects, a draw call for it is dispatched.

In Three.js this is built in and enabled by default. For instanced meshes, however, it works at the draw call level: either all instances are sent, or none of them are.

Although real per-instance culling is a little bit more complex, my first instinct was to add my own visibility logic GPU side, in the same compute shader I used to compute other per-instance traits. Something relatively simple, cheap and conservative, not necessarily an exact geometric culling.

Here is the full implementation of the visibility check function I ended up after some trials:

const computeVisibility = Fn(

([

worldPos = vec3(0), // instance position in world space

cameraMatrix = mat4(0), // projectionMatrix * matrixWorldInverse

fX = float(0), // projectionMatrix[0]

fY = float(0), // projectionMatrix[5]

r = float(0), // bounding sphere radius in world units for the grass blade

padNdcX = float(0), // extra paddings in NDC to hide camera rotation "lag" gaps

padNdcYNear = float(0),

padNdcYFar = float(0),

]) => {

const one = float(1);

const clip = cameraMatrix.mul(vec4(worldPos, 1)); // world space -> clip space

const invW = one.div(clip.w);

const ndc = clip.xyz.mul(invW); // clip space -> NDC

// proxy for depth in view space, works for WebGL and WebGPU

const eyeDepthAbs = clip.w.abs().max(EPSILON); // epsilon only to avoid div-by-zero, not to inflate radius

// project a world-space bounding sphere radius into NDC space

// farther away => smaller NDC radius.

const rNdcX = fX.mul(r).div(eyeDepthAbs).add(padNdcX);

const rNdcY = fY.mul(r).div(eyeDepthAbs);

const rNdcYNear = rNdcY.add(padNdcYNear);

const rNdcYFar = rNdcY.sub(padNdcYFar);

const visLeft = step(one.negate().sub(rNdcX), ndc.x);

const visRight = step(ndc.x, one.add(rNdcX));

const visX = visLeft.mul(visRight);

const visNear = step(one.negate().sub(rNdcYNear), ndc.y);

const visFar = step(ndc.y.add(rNdcYFar), one);

const visY = visNear.mul(visFar);

const visZ = step(-1, ndc.z).mul(step(ndc.z, 1)); // no Z padding

return visX.mul(visY).mul(visZ);

},

);It returns a single 0 or 1 flag per blade respectively for outside the padded frustum or inside.

The plan was to use this flag in order to avoid fragment work for blades that were outside the view.

Later on, I learned that this wasn’t as clever as I initially thought, or at least not in the way I had framed it.

Even without any custom culling, anything fully outside the frustum won’t generate fragments. The vertex shader may still run, but if it doesn’t intersect the clip volume, nothing gets rasterized, so the expensive part (fragment shading) doesn’t happen.

At first glance, my implementation might now look like pure redundancy, extra work without real benefit, but that’s not actually the case.

I built this test for a reason, but that doesn’t mean I can’t use it for a different one :)

My compute shader, other than this visibility check, takes care of positioning and wrapping instances, sampling textures to determine where grass is allowed on the map, evaluating noise-driven wind, handling trail logic, and more.

It does all of this for every instance, every other frame (a deliberate trade: half the compute work, same perceived motion), even though roughly only one third of the blades are visible at any given moment.

So instead of thinking in terms of culling, I started thinking in terms of early refusal.

If I already know that a blade shouldn’t matter, I can stop spending effort on it as early as possible, ideally before it reaches the expensive parts of the pipeline.

This introduces a bit of branching, and GPUs are not particularly happy about that, but in this case, the benefits clearly outweighed the costs.

The benefits don’t stop there though.

I combine this frustum check with stochastic thinning (more on this in the next section) and alpha mapping (where grass is allowed on the map).

In earlier versions, I made the mistake of using this flag inside the fragment shader and calling discard. That felt

logical at the time: if it shouldn’t be drawn, just discard it. But discard happens after the fragment shader has already run.

The GPU still did the work, I just told it to throw the result away. In a system already dominated by overdraw, that’s about

the worst thing you can do.

The better option turned out to be much simpler.

Instead of discarding fragments, I move the vertices of invisible blades far away from the camera, along the camera’s forward direction. Effectively, those instances no longer intersect the frustum at all. No triangles make it to rasterization, no fragments are generated, and the fragment shader never runs for them.

class GrassMaterial extends SpriteNodeMaterial {

constructor() {

// ...

const offscreenOffset = uniforms.uCameraForward

.mul(INFINITY)

.mul(float(1).sub(isVisible));

this.positionNode = bladePosition

.add(offscreenOffset)

.add(/* ...wind, etc... */);

// ...

}

}It’s not true GPU culling in the sense of removing instances from the draw call. The vertex shader still runs, and the instance is still technically there. But for my workload, where fragment cost is the real enemy, this small trick makes a very real difference.

That’s where the gain actually comes from: not from “outsmarting” the renderer, but from aligning my own logic with how the pipeline really behaves.

One could rightfully ask: “Why not actual culling with compaction and indirect draw calls?”

I did briefly explore it: fully compacting visible instances using a prefix sum compact algorithm and indirect draws.

The theory was quite clear after some pen-and-paper work the old-fashioned way, and it’s a powerful approach. In practice, it’s also a completely different level of complexity: parallel algorithms, synchronization, multiple passes, and a lot more surface area for bugs.

I gave it a try one evening, got incorrect results and frame drops, and decided to step back. I might give it another try in the future, if not out of necessity, then perhaps out of sheer curiosity, but for now, I’ll simply leave it be.

For the curious, here is the link to my attempted implementation.

Ignore it, laugh at it, learn from my mistakes, up to you :)

To sum things up: vertex processing was never my bottleneck, overdraw was. The combination of early visibility decisions, moving

invisible geometry out of the frustum, and avoiding discard already removed a large amount of wasted work. The system was fast,

stable, and simple enough to reason about.

Sometimes the right optimization is not the most advanced one, it’s the one that solves your problem without turning the system into something you’re afraid to touch six months later.

3. Less grass, same feeling

Grass is one of those things where the brain does a lot of the work for you. You don’t count blades, you read density, motion, and color. As long as those cues are there, the field still feels full, even if a surprising amount of geometry is missing.

That observation opened the door to another small but very effective trick: stochastic thinning.

Instead of trying to render every blade everywhere, I let probability do some of the work. Close to the player, density stays intact. As you move farther away, blades start disappearing, not in rings, not in obvious patterns, but randomly, in a way that stays stable over time.

It’s not LOD, and it’s not culling. It’s simply accepting that, beyond a certain distance, less grass can feel exactly the same.

At its core, the idea turned out to be very simple.

For each blade, I look at its distance from the player and remap it into a normalized 0 → 1 range. Inside a near

radius (R0), blades are always kept. Beyond a far radius (R1), only a small percentage survives (pMin). In between, the

probability fades smoothly.

As with the visibility check from the previous section, here’s the full implementation of the stochastic thinning function I ended up with:

const computeStochasticKeep = Fn(

([

worldPos = vec3(0),

playerPosition = vec3(0),

R0 = float(0), // full density radius

R1 = float(0), // far radius, faded density

pMin = float(0), // keep probability at edge

]) => {

// world-space radial thinning (no sqrt)

const dx = worldPos.x.sub(playerPosition.x);

const dz = worldPos.z.sub(playerPosition.z);

const distSq = dx.mul(dx).add(dz.mul(dz));

// use squares to avoid square root, a bit cheaper

const R0Sq = R0.mul(R0);

const R1Sq = R1.mul(R1);

// 0 inside R0, 1 at/after R1

const t = distSq

.sub(R0Sq)

.div(max(R1Sq.sub(R0Sq), EPSILON)) // epsilon avoids div-by-zero

.clamp();

// keep probability from 1 -> pMin

const p = mix(1, pMin, t);

// deterministic random number per instance (stable under wrap)

const rnd = hash(float(instanceIndex).mul(0.73));

const keep = step(rnd, p);

return keep;

},

);The important part is not the math itself, but the properties it gives you.

Because the random value is derived from instanceIndex, thinning is deterministic. Blades don’t flicker or pop as

the camera moves. Because the fade happens over a radius instead of a hard cutoff, density transitions feel natural.

And because everything works on distance squared, the whole thing stays cheap enough.

Once this was in place, tuning it became almost intuitive. A handful of values were enough to shape the entire field: how far full density extends, how quickly it thins out, and how sparse the far grass becomes.

With my current values: a roughly 130×130 unit patch holding about 1.18 million blades, a dense inner radius of 10

units (R0 = 10), a thinning radius of 60 (R1 = 60), and a minimum keep probability of 10% (pMin = 0.1), more than half of

the blades are removed on average across the whole patch (not just inside the frustum).

As Nole (Novak Djokovic) would say: “Not too bad” :)

Crucially, this doesn’t happen in isolation. The result feeds straight into the same isVisible signal computed by the

visibility check from the previous section. Blades that fail thinning follow the same cheaper path through the rest

of the system.

I didn’t run clean A/B benchmarks here. The scene isn’t static enough for that, wind, camera motion, and other systems make timings noisy. What was immediately noticeable, though, was extra headroom. Fewer worst-case frames and more freedom to push density.

4. One face is enough

Up until now, all the work was about drawing less.

But there was still something quietly expensive happening everywhere, even for the blades that survived thinning and visibility checks: each blade was being drawn twice.

For a long time, that felt normal.

Grass blades are thin. You want to see them from both sides. Double-sided geometry sounds like the obvious choice, and for my early versions it was the obvious one. Each blade was a thin strip of geometry, rendered with two faces, bending nicely in the wind.

Visually, it made sense. Performance-wise, it was a silent tax.

Every blade contributed twice the fragments, twice the overdraw, twice the opportunity to waste work, and all of that stacked brutally once density went up. No amount of thinning or clever visibility logic could fully offset that.

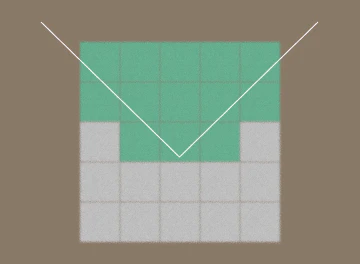

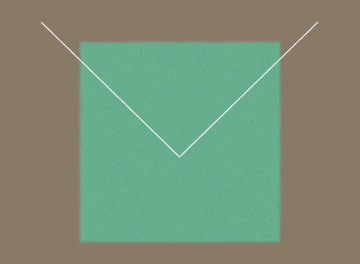

The moment I finally questioned this assumption I felt a bit uncomfortable, because the alternative sounded worse at first: sprites.

Sprites felt like cheating. Flat, fake, too “billboardy”, and yet, they solve exactly the problem I had.

A sprite always faces the camera, which means one face is enough.

Less blades with exaggerated width to better see how they stay camera-facing

Switching to a sprite-based material immediately removed half of the fragment work for every surviving blade. No second face. No back-facing fragments. No doubled overdraw. Just one surface doing the job.

It was one of those changes where nothing dramatic happens visually, but the system suddenly breathes better.

Of course, it wasn’t free.

By giving up double-sided geometry, I also gave up something I had been relying on without realizing it: orientation-based bending.

In the earlier versions, wind deformation was partly driven by rotating vertices around an axis. With sprites, that logic breaks down quickly. The blade still has a yaw, meaning it can rotate around the vertical axis, but pitch, which in my case was responsible for bending, becomes meaningless once the geometry always faces the camera.

The symptom was subtle but annoying. Wind direction started feeling inconsistent. As the camera moved, the same breeze appeared to change direction. It was not wrong mathematically, but it was wrong perceptually.

The solution was to stop thinking in terms of rotation and start thinking in terms of displacement.

Instead of rotating the blade geometry along the horizontal axes to simulate wind, I now offset vertices in world space, pushing them sideways based on a stable wind direction. The wind vector lives in the world, not in the blade’s local orientation, so it stays consistent no matter how the camera moves.

Of course that also came with its own trade-off. Too much displacement and the blades start stretching unnaturally, too little and the field feels lifeless.

Finding the balance took some tuning, but it was a trade I was happy to make. Ambient motion could stay subtle, while stronger gusts, the kind I wanted for moments of emphasis, could still exist without breaking the illusion.

In hindsight, this was probably the single biggest win in the whole system.

Not because sprites are fancy, but because they let everything else work better. Thinning, visibility decisions, and soft culling all benefit when each blade is only ever drawn once.

It is also worth mentioning that I opted for sprites because of their built-in camera-facing behavior, which meant I did

not have to implement it myself, and because they are unaffected by lighting, matching the simple shading model I was

already using with MeshBasicNodeMaterial.

5. This bad boy can fit so much data

With the bigger pieces finally falling into place, I allowed myself a small side quest.

Nothing was broken. Performance was already in a good place. This was not about fixing a bottleneck or chasing extra FPS. I was simply curious.

I had heard about bit packing before, but I had never really used it in practice. It always felt like one of those techniques you know exists, but only reach for when you absolutely have to. This felt like a good opportunity to finally understand it properly, on a system I already trusted.

At that point, each grass blade was already carrying quite a bit of state: offsets, scale, wind parameters, visibility,

noise factors. In earlier iterations, all of this lived across multiple vec4 buffers. In the current version, the same

information fits into a single vec4, plus one extra float for vertical displacement, with room left to spare.

That alone was not the motivation. What interested me was how this works, and when it actually makes sense.

The core idea is simple: not all data deserves the same precision.

A grass blade does not need a full float to say whether it is visible. It does not need perfect precision for a small rotation angle, a wind phase, or a noise factor that is already random by design. Most values live in tight ranges, or are binary choices. Instead of giving each one its own float, I treat a single float as a small container.

Each value is first mapped into a known range, then quantized into a fixed number of steps, stored at a specific offset, and later decoded back into an approximation. The loss of precision is intentional and controlled.

Conceptually, imagine starting from a single float that currently stores zero:

00000000 00000000 00000000 00000000Now suppose I want to store two things inside it:

- a visibility flag, either

0or1 - a yaw angle in the range

[0 .. 2π)

First, the flag. I reserve one bit at offset 0. Writing 1 into that slot simply flips the lowest bit:

00000000 00000000 00000000 00000001

↑

visibility flagNext, the angle. I decide that 7 bits are enough, which gives me 127 discrete steps over [0 .. 2π).

An angle like 45° is first converted to radians, then mapped to an integer code:

const angle = Math.PI / 4; // 45deg

const steps = 2 ** 7 - 1; // our 127 discrete steps for 7 bits

const normalized = angle / (2 * Math.PI); // map to range [0..1)

const quantized = Math.round(normalized * steps); // results in the number 16

// 16 in binary is 0010000 (7 bits because of our choice)And that is what I actually store, the integer 16, not the original angle. That integer code is written starting at

offset 1, right after the flag:

quantized angle

↓↓↓↓↓↓↓

00000000 00000000 00000000 00100001

↑

visibility flagThe final value is still just a single floating-point number. When unpacking, the process is reversed: extract the bits at each offset, convert them back into their original ranges, and accept the small approximation error that comes from quantization.

Even though this is a float, it works reliably because floats can represent integers exactly up to a certain size. As long as the packed payload stays below that threshold, values round-trip cleanly. I am not reinterpreting raw bits or touching exponent fields. I am encoding values arithmetically into a range the float can represent without ambiguity. Any loss of precision comes from quantization I chose, not from floating-point quirks.

In practice, this lets me pack things like:

- single-bit flag for visibility

- unit ranges for noise factors

- bounded ranges for wind vectors

- quantized scales and height offsets

all inside one float lane, while keeping the system predictable and easy to reason about.

Did this suddenly make the grass faster? Not really. That was never the point.

What it did give me was a better mental model. Bit packing stopped being an abstract idea and became something concrete I could use, debug, and trust. If I ever run into a system where memory layout or bandwidth really does matter, I will not be starting from zero. That alone made the detour worth it.

If you are curious, all the packing and unpacking helpers and underlying implementations live in this file that I reuse across systems.

6. A small shadow that caused big trouble

Because the grass is not affected by light, it tends to look a bit flat if left as is.

To break that monotony, I experimented with noise-driven color variation. It produced a pleasant, slightly anime-like look, but it was not quite what I was after. I wanted something stylized, not physically accurate, but also not fully blended into the terrain.

The fix was obvious: a touch of ambient occlusion.

Nothing fancy. Just a subtle darkening near the base of each blade to hint at contact with the ground and give the field some depth. This is not screen-space AO or anything global, just a tiny per-blade shading term. I had done this before, so I added it almost automatically.

After that, a few dots finally connected in my brain as I ran into a familiar problem.

In earlier versions, I was applying AO along the entire blade. Thin geometry plus dark shading at a distance is a great recipe for aliasing, especially once blades start collapsing to sub-pixel sizes. Blades began to shimmer. The grass gained depth, but lost stability.

This time I treated it more carefully.

Instead of occluding the whole blade, I limited AO to a small region near the base. The effect fades out quickly as you move up the blade, leaving the tip completely untouched. I also clamped both the radius and the intensity based on distance, so farther grass is not affected at all.

The result is deliberately understated. Close to the player, blades feel grounded. Far away, the field stays clean and stable. No dark speckling, no crawling edges, no extra noise competing with motion.

It did not change performance in any meaningful way. That was never the goal. It simply removed a visual distraction I had created for myself in the past.

As a side effect, it became a useful artistic control. By dialing the AO down even further, the grass shifts toward a more anime-like look. Pushing it slightly brings it back toward something more grounded. Same system, different mood.

More grounded - full AO intensity covering the whole patch

For my version, I settled somewhere in the middle. Grounded enough, calm enough, and it is nice to know I can slide that dial whenever I want.

7. The obvious solution I didn’t pick

It’s probably fair to ask a very reasonable question: Why not tiles?

While researching how grass is usually handled in games and real-time environments, tiling kept coming up as the default solution. The world is split into chunks, grass is attached to each tile, whole tiles are culled when they fall outside the frustum, LODs are added, and that’s often enough. It’s a solid, proven approach, and for many setups it’s absolutely the right one.

I did consider it. I even implemented a basic version. It worked, but it pushed the system toward a different set of trade-offs.

You gain real culling, geometry that never even reaches the pipeline when a tile is off-screen. You also open the door to classic LOD strategies. Those are real advantages, no question about it.

At the same time, new costs start to creep in.

Now there are multiple draw calls instead of one. Even with reasonably sized tiles, you’ll quickly end up juggling several of them per frame. You also have to decide how big a tile should be: too large and you lose the benefit of culling, too small and you increase overhead and management complexity.

More importantly, the mental model changes.

A lot of what I’m doing lives naturally at the instance level: per-blade visibility decisions, stochastic thinning, compute-driven updates, shared wind fields, alpha mapping. With tiles, I would either need additional buffers per tile, or some indirection layer to map blades to tiles and back, and keep all of that in sync. None of that is impossible, but it does push the system toward something heavier and harder to reason about.

I also noticed something else when I tried it.

Even when performance was fine on average, I occasionally saw small hitches, not dramatic frame drops, just tiny stutters, enough to break the feeling of smoothness. That could likely be improved with more time and care, but it reinforced a pattern I had already noticed during this project.

Simple systems tend to stay smooth.

The approach I ended up with is not “better” in a general sense. It’s just a better fit for my constraints: a fixed-height camera, a player-centric field of grass, a strong focus on visual continuity, and a desire to keep things predictable and easy to tweak.

One draw call.

One set of buffers.

Visibility and density handled explicitly.

No hidden heuristics.

That simplicity was intentional.

It’s not the solution I would recommend blindly, and it’s not the one I’d necessarily use in a different project. But for this world, at this scale, it let me move faster, experiment more freely, and keep the system approachable, which, for something I work on in my free time, matters more than theoretical perfection.

8. A quick trip down memory lane

Before wrapping things up, I’d like to take a short look back, not to extract lessons or frame this as a clean progression, but simply to give some context to how this system actually came together.

The very first version of the grass was about as simple as it gets.

A single blade made of a few triangles, instanced in a grid, subdivided just enough to bend, with a bit of noise in the vertex shader to fake wind, statically positioned. On screen, it looked… fine. Actually, it looked pretty nice. Enough to make me think I was on the right track.

But I wanted to have grass everywhere so instinctively I scaled it up.

More blades, bigger patch, same logic, and suddenly everything fell apart. Frame times spiked, fans kicked in, and the machine started sounding like it had something personal against me. The scene was still basically empty, yet the grass alone was already pushing things too far. That was the first real reality check.

The second iteration came almost immediately and not from some clever insight. It came from stubbornness and a decision to dig deeper instead of giving up.

That’s when I really started learning TSL properly. I moved more logic to the GPU, set up SSBOs for the first time, and introduced compute shaders to handle per-instance work instead of pushing everything through the vertex stage. Along the way, I made some conscious trade-offs: giving up real lighting in favor of a simpler material, experimenting with GPU-side visibility checks, and trying to be more explicit about where work was actually happening.

Not all of those choices were good ones.

That early soft GPU culling logic, for example, was technically doing what I asked, but I paired it with fragment-level

discard, which meant I was often making things worse instead of better. On top of that, the geometry was still

double-sided, which quietly doubled my overdraw before I even realized it. Stochastic thinning came later and helped

bring things back under control, but by that point the system was already a collection of compromises.

Second iteration, currently live at the time of writing

That version is the one that’s been live for a while now. It works, it’s stable, and for a long time it felt “good enough”. But the grass was also much sparser than what I had originally imagined, and I knew I was still leaving a lot on the table.

The version that inspired this article did not start from scratch. It builds directly on the previous system.

The difference is experience. By the time I revisited it, I had a much clearer picture of where the real costs were, how the pipeline actually behaved, and which trade-offs were worth making. Instead of layering fixes on top of fixes, I could finally step back, simplify aggressively, and push density without immediately paying for it.

There’s still a long way to go. I’m very aware of that, but the gap between what I imagined at the beginning and what I can actually run today has shrunk a lot, and that alone made the whole detour worth it.

Closing thoughts

This grass system took far more time than I ever expected.

Some ideas worked immediately. Others looked promising on paper and turned out to be dead ends. A few things only made sense months later, once I had enough context to recognize why they mattered in the first place. That’s probably the part I didn’t fully appreciate at the beginning: how much of this kind of work is less about finding the right technique, and more about understanding when a technique actually applies.

The version I’m working on now isn’t live yet, and it’s not some final destination either. It’s just the first time the grass really matches the image I had in my head when Revo was nothing more than an empty scene and a moving sphere. It’s dense, calm, responsive, and, most importantly, it doesn’t feel like it’s constantly fighting the GPU.

None of this is meant as a blueprint. The choices I made are deeply tied to my constraints: the camera, the scale, the style, the fact that this is a personal project I work on in bursts of energy between other things. In a different world, with different requirements, I’d probably make very different decisions.

Still, sharing this felt worthwhile.

Not because every trick here is groundbreaking, but because this is what it actually looked like to build something iteratively, get it wrong multiple times, and slowly get closer by paying attention to where the work was really going.

If any part of this helps you avoid a detour, or at least recognize one earlier, then writing it was time well spent.

For now, the grass finally feels right.

And that’s a nice place to pause :)

If you’re curious about how all of this comes together in practice, the grass system described here lives in a single file in the Revo codebase. It’s not meant as a reference implementation or a drop-in solution, but it might be useful to see how these ideas connect in the real project.

Grass.ts (may be subject to changes)

Explore more

A few resources that helped shape or complement this exploration:

How do Major Video Games Render Grass? — Simondev

Ghost of Tsushima Procedural Grass — GDC Vault

How Do Games Render So Much Grass? — Acerola

What I Did To Optimize My Game’s Grass — Acerola

Modern Foliage Renderings — Acerola

Infinite grass - New portfolio - Devlog 2 — Bruno Simon

Blelloch Scan - Intro to Parallel Programming — Udacity